FRC® Course Review

This past weekend I attended a continuing education course entitled Functional Range Conditioning (FRC®), one of several courses offered by Functional Anatomy Seminars that was developed by Canadian chiropractor and educator Dr. Andreo Spina. Earlier this year I also attended the Functional Range Release (FR®) course for the upper limb, which is a soft tissue assessment and treatment system for manual therapists. The courses have been rapidly growing in popularity over the past couple of years so I was more than excited to dive in.

This post will be my personal review of the FRC® course based on my interpretation of the subject material as it was taught. For further in-depth information, you may sign up for a Functional Anatomy Seminar which will also give you access to archives of educational content including video demonstrations. Additionally, to read a brilliant review about the FR® manual therapy course I point you in the direction of the prolific Dr. Aaron Swanson who blogged about the Upper Limb seminar last year.

FRC® is a joint-training system designed to:

increase your body’s capacity for active mobility,

bulletproof and protect your joints, and

to have an efficiently operating nervous system to control your body healthily.

We initially spent a significant amount of time reviewing the biochemical, physiological and histological reasoning behind the FRC® system, and rightfully so as these principles laid the foundation for why movements were performed as they were. I won’t delve into these principles as the material can be very esoteric and detailed, but I will mention a couple of really important ones that resonated with me.

Force is the language of cells.

Force determines the outcome of how cells, fibers and ground substance develops into tissues, bone, fascia, tendon, etc. Therefore when recovering from an injury, the way we “communicate” to the injured tissue (whether it’s force through movement or applied manually) influences the way that tissue heals. Specific rehab interventions to injured tissue, when applied with respect to force and direction, can dictate the proteins that are produced and the resultant anatomy that develops through mechanical input.

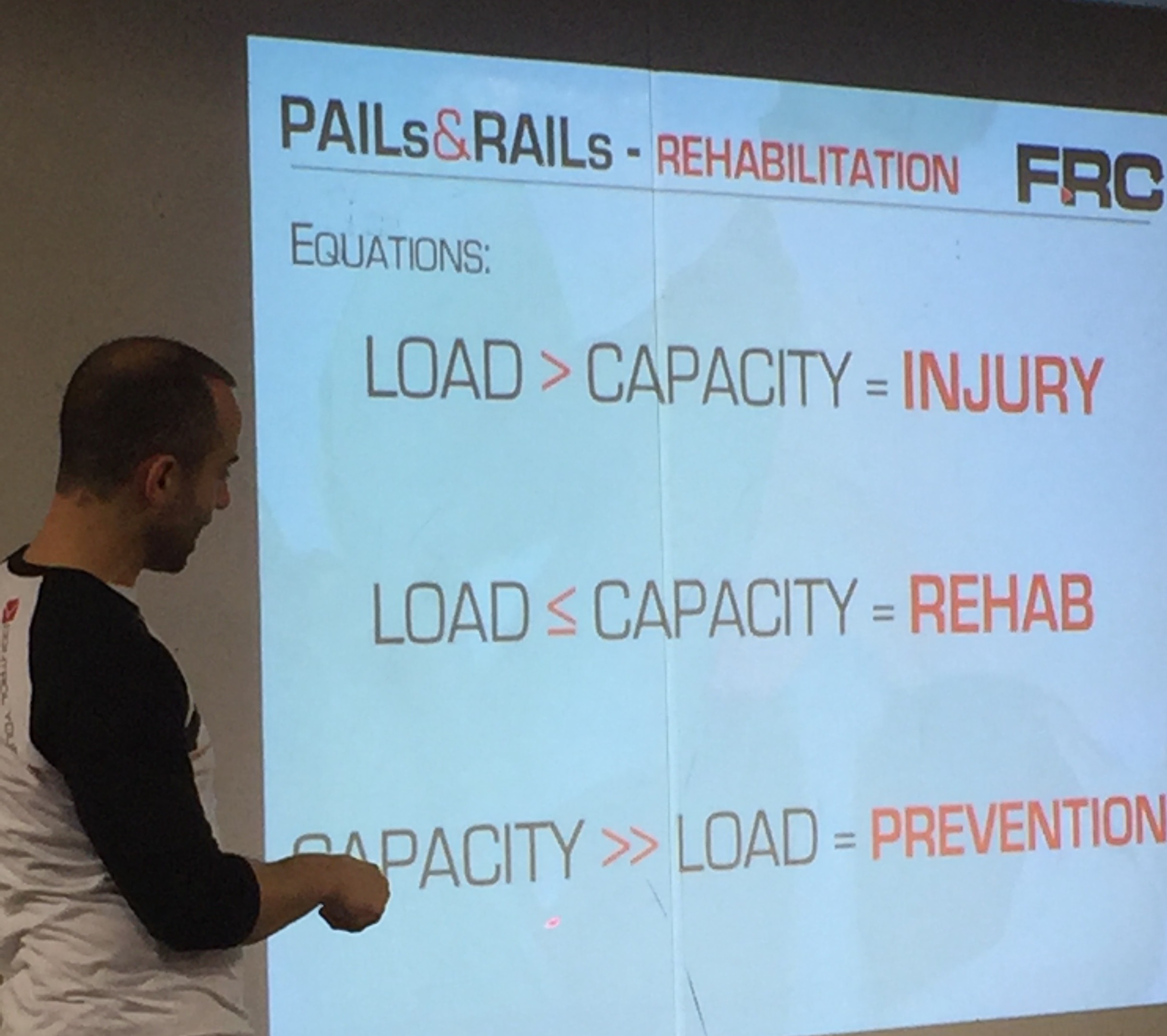

When FORCE > LOAD, the result is INJURY. The first job of rehab is to guide the way injured tissue is healing.

You do so by gradually managing a slight level of loading to the injured tissue, not exceeding it's capacity, and gradually bumping up that threshold. Movement is an effective inflammatory modulator in injured tissue.

Dr. Spina breaking it down.

In addition to the didactic portion of the seminar, we spent considerable time performing various mobility training drills designed to take our upper and lower body joints through many different movements and positions, some more unorthodox than others. Applying different types of isometric contractions (or PAILs and RAILs, which stand for progressive/regressive angular isometric loading) served to deepen our joints and bodies into these positions, which felt somewhere in between exercising while stretching simultaneously. Going through these drills felt like nothing I've experienced before and allowed me to gain a better sense of body awareness and proprioception I had yet to encounter.

I should've known to turn the phone sideways when taking videos...

Gems from the Weekend

Dr. Spina is probably one of the funniest continuing education speakers I’ve encountered, especially when it comes to dispelling what he interprets as outdated rehab methodology. I took some paraphrased notes on some of the one-liners he had that either resonated with me clinically or just plain cracked me up.

“The better you are at athlete, the worse you are at human. Oh, that NBA player can 360 windmill dunk? Tell that MF to touch his toes, I bet he can’t.”

There’s a misunderstanding that professional athletes are these physically flawless human beings with optimally functioning muscles and joints. The reality of the matter is that more often than not, training the body to optimize athletic performance and specializing in certain athletic skill sets comes at the cost of joint health. If the human shoulder was designed to brachiate (or swing from branch to branch with our arms), a major league pitcher with excessive shoulder external rotation that trains to throw an object 100+ mph is going to cause serious injury. As a result, they lose the ability to perform many basic human functions.

““The better you are at Athlete, the worse you are at Human.””

“Passive mobility doesn’t necessarily translate to active movement. FRC training is to capture passive mobility and activate it.”

Being really flexible and bendy doesn’t necessarily mean you can control your body through those ranges. You may be really stretchy but if you don’t have ownership over those extreme ranges of motion, how can your body actively call upon those ranges when you need it?

“Movements don’t exist.”

Dr. Spina made many references to Instagram and other popular social media platforms where people can show off their abilities to perform really sexy-looking movements, and thus receive social validation (i.e. comments, likes, etc.). People see these movements and feel like they need to do them too, for social validation or because they think that performing a really difficult movement always translates to healthy functioning and ability. It’s gotten to the point where performing a movement itself becomes to goal, as opposed to equipping yourself with joint health, tissue resiliency and proper motor control. The latter enables you to perform movements that are specific to your goals. The goal should not be to perform arbitrarily-defined movements that your body may not be physically prepared to do.

“There’s no such thing as a (insert anatomical structure here)”

Dr. Spina, despite his extensive knowledge of human anatomy and function will often refer to certain muscle groups as simply “stuff” on purpose. He has a physiological basis for doing so, a term he calls “BioFlow” (which I won’t get into here). He purports that oftentimes we have these preconceived notions of how certain body parts (muscle vs. ligament vs. tendon vs. fascia) should function in the body, and that these are hard unchanging rules. Such thinking may tend to compartmentalize our clinical thought processes into small boxes and we adhere to these rules based on arbitrary anatomical nomenclature.

For example, textbook kinesiology says that the iliotibial band is a knee flexor at 30+ degrees of knee flexion and a knee extensor at angles less than 30 degrees. Or that the MCL of the knee extends from the medial epicondyle of the femur to the medial condyle of the tibia. These structures are defined as such through cadaveric studies whereupon function is assigned based on observed anatomical landmarks, but these functions may not necessarily apply in living humans. Hence, "there's no such thing as an ITB (by the textbook definition). Your MCL (by the textbook definition) does not exist."

“You will always regret not training in the position you get injured in.”

When someone gets injured in a certain position, say an ankle inversion sprain, one might think he/she needs to avoid inversion indefinitely and that any movement that occurs in ankle inversion is harmful. In reality, at the appropriate time we should actually be training patients MORE in positions of previous injury (barring acute inflammation or excessive pain) to build resilience in those weak points.

““You will always regret not training in the position you get injured in.””

“Your injury doesn’t give a sh*t if you don’t have time to take care of it.”

Doing the exercises your physical therapist gives you for homework sucks. They can be boring and time-consuming. We often want to make concessions or short-cuts to make the process easier, more conducive to our busy work schedules, to accommodate our feelings of boredom or to make room for more fitness-related goals.

Why do we do this when it comes to the health of our bodies? When one consults a lawyer for legal advice, does one pick and choose the advice that fits best into one’s schedule or is most accommodating? No! There is a correct course of action to take, with sub-optimal results that occur as a consequence when the advice is not heeded. Like going to jail.

Your torn hamstring doesn’t care if you don’t have time to treat it correctly. It will continue being a torn hamstring and will continue to be painful.

Other Noteworthy Principles

On cramping prevention: Graded exposure of certain joints to gradually increasing loads for gradually increasing durations in potentially cramp-inducing positions can build cramp resilience. The goal is to familiarize your nervous system with inefficient positions in order to make them more efficient and to give your muscles the ability to contract when called upon.

Eccentric Neural Grooving: Eccentric loading exercises give the necessary stimulus to muscles to get longer by adding sarcomeres in length. Static stretching doesn’t produce a load-bearing stimulus to the cells. Use eccentric training as a preventative intervention to tendinopathy rather than waiting for it to occur.

Overall I found both courses to be very educational experiences whose principles I will be frequently incorporating into my practice. The Functional Anatomy Seminars were a refreshing departure from topics I’ve recently been reading about or attending courses for, such as regional interdependence, mobility vs. stability, the biopsychosocial model of pain, etc. They allowed me to look at rehabilitation principles with more of a focus on what is occurring from a biochemical and histological (or tissue structure) perspective and I recommend these courses to health care professionals or those in the wellness industry as your scope of practice allows.

Special thanks to Perfect Stride Physical Therapy and Crossfit Union Square for hosting!